Anna May Wong

National Archives News

WASHINGTON, March 30, 2021 — Recent acts of violence against Asian Americans across the country have underscored the notion of being perceived as a “perpetual foreigner” in one’s home country.

But this is nothing new. The “othering” of immigrant groups is long rooted in American history.

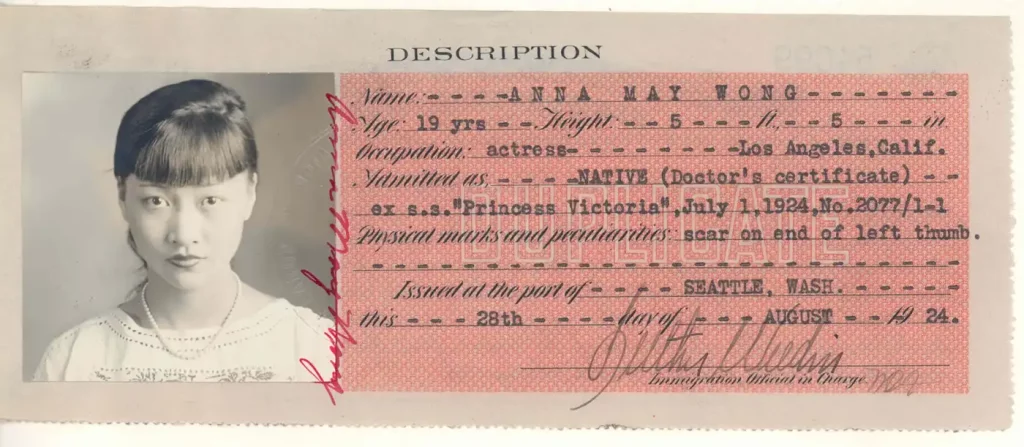

Trailblazing Chinese American actress Anna May Wong may be remembered from Hollywood movie posters from the 1920s, but here at the National Archives, she appears on a rather less glamorous document: a Certificate of Identity issued by the United States Government.

Although Wong was a third-generation American and spoke English as her native language, the U.S. Government nonetheless viewed all persons with Chinese origins as foreigners. From 1882 to 1943 the United States Government severely curtailed immigration from China to the United States, passing a series of laws whose result was the documentation of Chinese nationals and Chinese Americans.

“You can see that Anna May Wong’s certificate is red, so we know it was issued under the Department of Commerce and Labor regulation adopted on March 19, 1909, which related to certificates of identity issued to Chinese nationals and Chinese Americans entering the United States through mainland U.S. and Canadian ports,” said Elizabeth Burnes, an archivist at the National Archives at Kansas City. Burnes is the National Archives’ Subject Matter Expert in immigration records. “Red certificates listed each holder’s name, age, height, occupation, admission status under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, physical marks, and port of issuance.”

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 prohibited the immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law was extended repeatedly until it was finally repealed by the Magnuson Act of 1943. Over time, through amendments, the law required all ethnic Chinese to apply for entry and reentry into the United States, despite their country of origin.

On the front, the certificate contains a photograph of Anna May Wong at age 19. Her occupation is listed as “actress.”

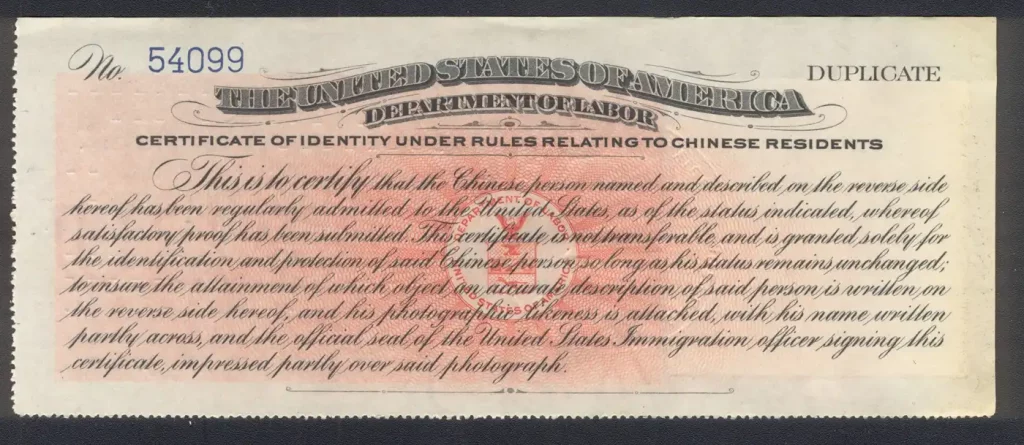

On the back, the document reads:

This is to certify that the Chinese person named and described on the reverse side hereof has been regularly admitted to the United States, as of the status indicated, whereof satisfactory proof has been submitted. This certificate is not transferable, and is granted solely for the identification and protection of said Chinese person so long as his status remains unchanged; to insure the attainment of which object an accurate description of said person is written on the reverse side hereof, and his photograph likeness is attached, with his name written partly across, and the official seal of the United States Immigration officer signing this certificate, impressed partly over said photograph.

“The Certificates of Identity were an extension of requirements that had slowly built out from the original 1882 exclusion law,” Burnes said. “The 1892 Geary Act had added requirements for certifying residency by allowing Chinese laborers to travel to China and reenter the United States, but its provisions were otherwise more restrictive than preceding laws. The act required Chinese people to register and secure a certificate as proof of their right to be in the United States. Imprisonment or deportation were the penalties for those who failed to have the required papers or witnesses.”

Although her family had lived in the United States since the 1850s, the federal government—and Hollywood—considered Wong a foreigner solely because of her race. Even as American audiences were eager to consume stories featuring Asian characters, anti-miscegenation laws and the 1930 Motion Picture Production Code (created by Will H. Hays) prevented movies from depicting marriages and on-screen kisses between actors of different races. Thus, despite her talent and star power, Wong was relegated to supporting roles while the lead roles were played by white actors in yellowface.

Many of the records created to implement the Chinese exclusion laws are now in the custody of the National Archives and have been digitized. The records are a major resource of Chinese immigration and Chinese American travel, trade, and social history from the late 19th to mid-20th century.

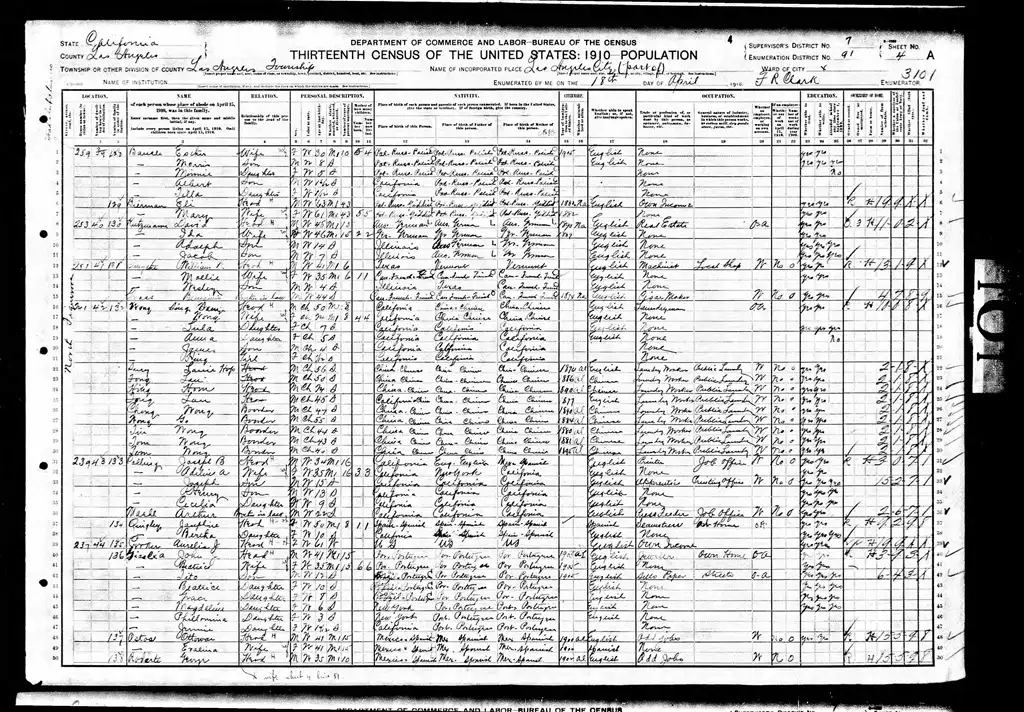

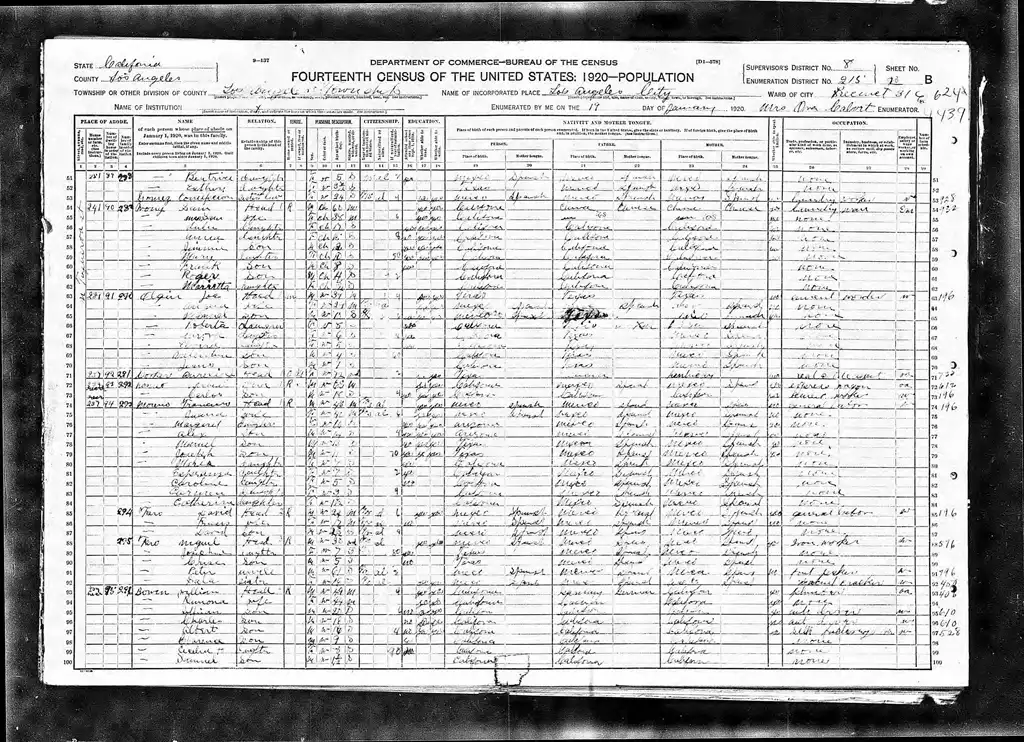

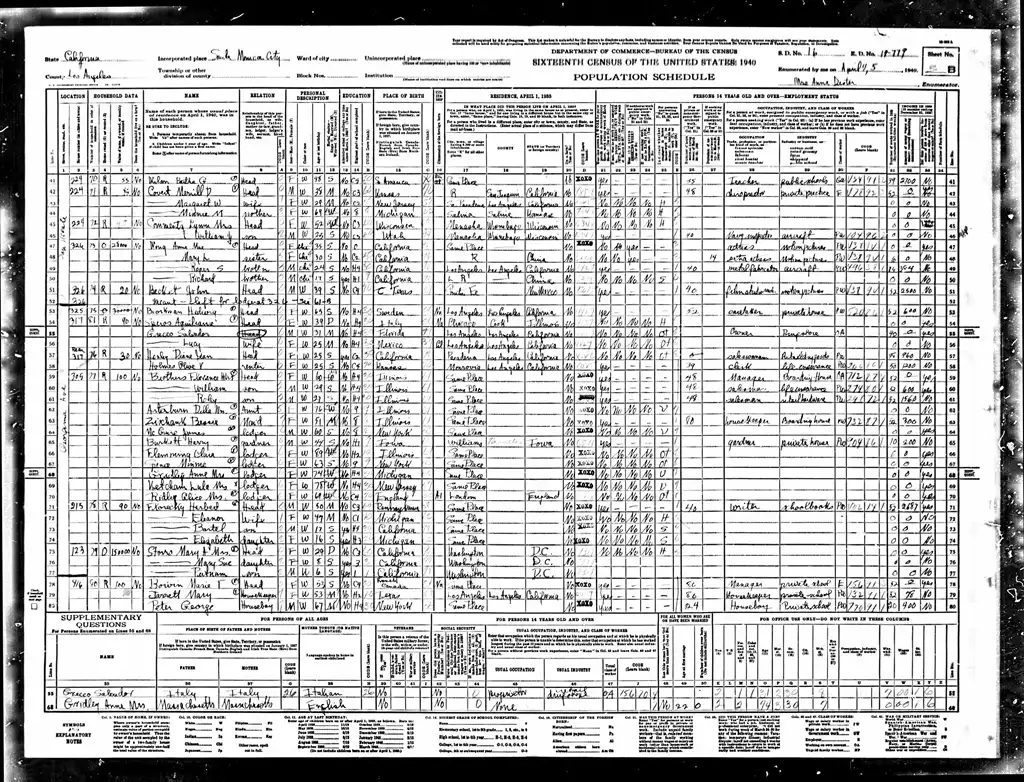

Another valuable resource for genealogists is the United States federal census. Wong appears in four: 1910, 1920, 1940, and 1950. Frustrated by being pigeon-holed into roles that emphasized stereotypes of Asian women, Wong moved to Europe in 1928 and lived there for a period of time, which may explain her absence in the 1930 federal census. Wong died of a heart attack in 1961 at the age of 56.

You can learn more about the Chinese American experience on the Chinese Heritage page on Archives.gov. You can also help us tag and transcribe Chinese heritage records as a citizen archivist.

Read more about one Chinese immigrant’s harrowing experience in this Spring 2004 Prologue article “An Alleged Wife: One Immigrant in the Chinese Exclusion Era.”

发表回复