(Portrait of Chiang Yu Tie, photograph taken in 1980.)

Born into a wealthy and politically conservative family in Zhejiang Province, China, Chiang went on to study European painting at the Xinxi State Academy of Painting in Chongqing despite her family’s disapproval, graduating in 1945. After falling ill three years later, Chiang migrated to Indonesia in 1948, where she eventually settled in Bandung as an art teacher and founded her own painting studio called Rumah Rumput.

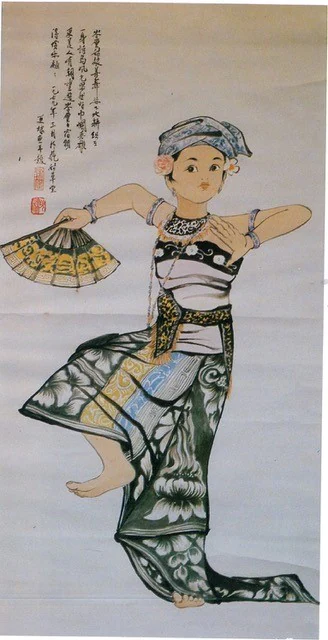

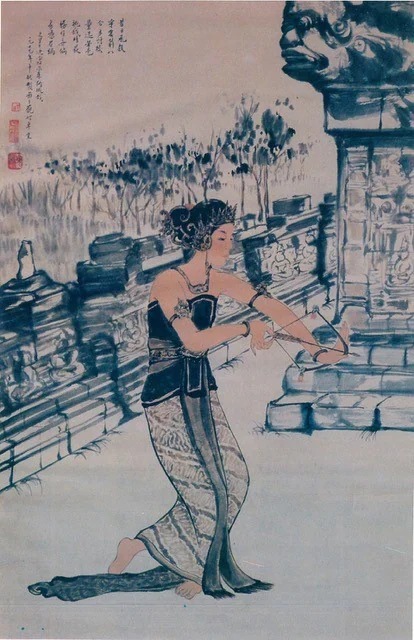

Like many of her contemporaries, Chiang’s paintings often feature Balinese landscapes and dancing Balinese women. The popularity of Bali as a subject matter amongst Chinese émigré artists in Southeast Asia speaks to their unique frame of mind, which encompassed a fascination for the exotic new world they now found themselves in, and a desire to express as authentically as possible this local reality, in an artistic language familiar to them. Oei attests to this endeavour to attain a true and faithful image of Bali, without its “make-up” (tanpa make-up):

“In fact, there are two versions of Bali, one being the Bali that is known by travellers, with all its make-up, designed to show off to tourists…Then there is also a real and genuine Bali, which is often unknown to visitors, because it is difficult to find, and the road is narrow…”

However authentic, this dualistic vision of Bali, distilled through the othering, touristic gaze of Chinese artists, would occupy an influential position in burgeoning national, and international, imaginaries of Bali, and more broadly, Indonesia.

In applying a feminist reading of Chiang’s works, however, we are invited to consider how the construction of a national imagination of Indonesia is also inflected by gendered difference. Are there, perhaps, alternative ways of cultivating a sense of Indonesian cultural identity that not only permits ethnic diversity, but also shifts away from the troubled and deeply gendered narratives of a singular artistic genius, or an exclusive chronology of “stylistically original”, representative works from (male) artists?

As we revisit Chiang’s works, we are offered an alternative point of view that defies rigid categories of colonial and anti-colonial time as well as patriarchal valuations of “good” art and “Indonesian” art in terms of originality, genius, and rivalry. In a painting titled, Kuda Lari (Galloping Horse), Chiang’s inscription quite literally poses a question to its viewers, reflecting on the constructed notion of artistic originality:

“Day after day, two years have already passed…The new meets old. The old “horse” is elevated by a “mountain”. An artist is just a creator. Who knows, what do you think?”

Chiang is likely to be referring to the idea of developing an individual art style through a discerning approach to imitation, which dates to Qing Dynasty China. Certainly, her chosen subject—a galloping horse—is one which bears a long lineage in Chinese art. In this sense, her work testifies to the presence of a Chinese line of thought in the history of Indonesian art. Viewed in hindsight, with a heightened mindfulness toward the exclusionary nature of canonical history, her paintings provide respite from totalising, gendered narratives of nationhood and post-colonial identity, offering an expanded definition of “the artist”, and who could lay claim to that title.

(Chiang Yu Tie, Galloping Horse, 1970, ink on paper, dimensions unknown. Private collection. Reproduced with permission from Teng Mu Yen, 2022.)

Many of her retellings of wayang stories also offer a space in which a feminine sensibility may reside. In a work painted in 1979, titled Srikandi dalam sayembara panahan (Srikandi in an archery competition), Chiang depicts Srikandi, a character from Javanese wayang born as a male but later transformed into a female (although the gender transition is reversed in the Hindu epic Mahabharata), who has been retrospectively turned into an icon of feminism and women’s emancipation in Indonesia. An inscription in the upper left-hand side details the story of the heroine in first-person narration:

“I used to be a student of archery. Now that I am skilled, let’s compete. If I should lose, I will become your concubine.”

An English translation provided in the exhibition catalogue adds a final line: “…but if I were victorious, I would refuse to give [my] hand to thee.”

Accompanied by defiant first-person inscriptions that seem to divulge the artist’s personal voice, Chiang’s selective renderings of wayang characters leave us to wonder about the hidden workings of women’s agency in the transmission of stories and images across time and space, outside of the established canon of Indonesian art history. This resistance against masculinised, nationalistic grand narratives is, in part, also generated as we connect with such works in the present-day. It is between Oei and Chiang’s practice in the twentieth century, and our patient, persistent attempts to revisit their works with an open-mindedness and receptivity, that we find capacity to dismantle those totalising narratives that so rigidly police our ideas of who can and should be a modern Indonesian artist, and what modern Indonesian art should look like.

Undoubtedly, more research is required to recover such stories and figures lost to canonical history—the translation of Oei’s work marks only a preliminary foray into the subject matter. Even so, the ripples of their impact can be gleaned today: in 2012, over a decade after her passing, 51 paintings by students, many women, taught by Chiang and her daughter, Teng Mu Yin, were exhibited by the Ikatan Wanita Pelukis Indonesia (Association of Indonesian Women Painters) in Bandung.

发表回复